Weeknotes June 16th-23rd

It is officially too hot

When I moved to Connecticut to become a postdoc at Yale, everybody warned me that the winter was going to be the hard bit. I would like to state, for the record: they were wrong. The dark was not great, but the snow was fun! The summer, on the other hand, is no joke. It has been over 30 degrees everyday this week and I have been riding the struggle bus. Having spent my whole life in England, I am not built for the heat and I do not own enough summer clothing. It is, however, only 3 weeks until I’m home for a glorious rainy English summer, and it gave me an excuse to lie down and watch Taylor at Wembley on a TikTok live yesterday, so I will not complain too much.

Anyway on with the notes.

Things I worked on

The Ethics of the Rapid Digitisation of Healthcare paper. The WHO Bulletin asked me to write a paper about the “ethics of the rapid digitisation of healthcare” which is due this week. I have been trying to use this as an opportunity to move the conversation about the ethics of digital health beyond just conversations about privacy or safety etc. and instead to highlight the ethical implications that only become apparent when one takes a ‘Birds Eye’ (high level of abstraction) view of the system. This is a fun task, but also a hard ask as the WHO policy and practice papers are only 3000 words with 50 references and I could probably write another PhD thesis on this topic. Hopefully, I will finish the paper today. The introduction is below:

Variously referred to as ‘e-health,’ ‘health 2.0’, ‘m-health’, or the ‘algorithmic’ revolution, the impact of digital technologies from mobile applications (‘apps’), to wearable devices, clinical decision support software, and online symptom checkers, on healthcare is undeniable. Today, automatic sensors can continuously – and painlessly - monitor the blood glucose levels of diabetic patients; Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems can estimate bone age, diagnose retinal disease, or quantify cardiac risk with greater consistency, speed, and reproducibility than humans; those most at risk of novel diseases can be identified and notified in near real-time; and those in remote locations can access world class care from home. Clearly, the digitisation of healthcare (henceforth digitised healthcare) represents a significant opportunity for saving and improving lives that should not be missed or wasted. Yet, this opportunity does not come without risk.

As enthusiasm for the potential benefits of digitised healthcare has grown, so too has concern regarding the safety of mobile apps; the accuracy of online information; the potential for AI systems to be biased; the threat to privacy posed by excessive online surveillance; and more. In response, a plethora of specific ‘technical fixes’ to these risks have been developed. For example, there are now multiple frameworks available for assessing the safety and efficacy of mobile apps, several known techniques for de-biasing datasets or handling data missingness, and numerous ‘privacy-enhancing technologies’. All such efforts are worthwhile and help, on a small scale, to ensure there is a proportionate balance between the benefits and risks of digitised healthcare. However, by focusing excessively on the ‘quantifiable’, and subsequently ‘fixable’, risks of the rapid digitisation of healthcare, attention has been diverted away from the less quantifiable, more normative, but larger-scale ethical risks associated with the re-ontologising (or fundamentally transforming) potential of digitised healthcare.

The full scale ethical implications of the digitisation of healthcare, are revealed only at the systemic or macro level of abstraction. In other words, the full scale ethical implications of digitised healthcare are not revealed by analysing the implications of each new digital health innovation (e.g., apps, wearables, symptom checkers) in isolation, but rather by simultaneously (a) analysing their combined impact on the fundamental elements of any healthcare system (e.g., empathy, caring, responsibility, accountability, equity, trust); and (b) revealing the consequential paradigmatic shift in the nature of healthcare brought about by a collision of technology, neoliberalism, capitalism, and everyday medicalisation. Thus, it is the purpose of the following pages to pursue this analysis. More specifically, section two discusses why the digitisation of healthcare is about more than a shift from paper to data; section three analyses the consequences of this shift for the definitions of health vs. illness, knowledge about the body, equity and the availability/accessibility of care, and trust in the healthcare system; and section four concludes the analysis outlining what needs to be done to ensure policymakers and healthcare system designers remain mindful of these macro-level ethical consequences as they continue to pursue the many potential benefits of digitised healthcare.

Comment on SciTech Committee Report on AI. At the end of May The UK Science, Innovation and Technology Committee published its last report for its inquiry into the governance of Artificial Intelligence, examining domestic and international developments in the governance and regulation of AI. Some colleagues asked if I would be interested in writing a comment on the report - comparing it to the EU AI Act and the US Executive Order on AI and, obviously, the answer to that question was yes. So I have spent the last few days working on a fast draft of this comment. I hope to finish it by the middle of this week.

AI in Healthcare Conferences. I am currently co-organising two major events on the topic of AI in healthcare, one three-day symposium in Venice in November, and one two-day workshop in Yale at the end of August. This week I’ve spent a lot of time finalising the agenda of both - agreeing who is going to speak on what etc. We have now got a *fantastic* line up for both. The planned keynotes for Venice are below. if you’re a junior researcher you can apply for one of 8 fully funded fellowships to attend (please apply even if you think you don’t need the funding - spaces are limited because the event is on an island so the only way to attend is by applying for a fellowship).

Effy Vayena "The ethics of AI in Healthcare"

Amelia Fiske "AI and global health equity: how can we move from promise to practice"

Angeliki Kerasidou "AI and Public Trust"

Elaine Nsoesie "AI and the Social Determinants of Health"

Hutan Ashrafian "The Challenges of real-world implementation - turbocharging AI in clinical practice"

Charlotte Blease "Open AI meets Open Notes: Generative AI and clinical documentation"

Leo Celi "AI in Low Resource Settings"

Sandeep Reddy "Harmonizing regulation of AI in healthcare globally"

Edits to three papers. My colleagues at the DEC continue to produce brilliant work on the regulation of AI in insurance, brain implants, and what it means to be an “AI ethicist.” I’ve been working on editing the requisite papers and hope they will be pre-printed soon.

Fellowships. If you’ve ready my weeknotes before you might be aware that I am currently in the delightful postdoc stage of applying for fellowship funding. To prep for this I had to take a three hour Yale course (despite having applied successfully for many grants in the UK - things that happened on the other side of the Atlantic don’t count apparently), which I did on Tuesday, and since I have been working on iterating budgets and agreeing on intra and inter-university collaborations - all the fun administrative stuff that has to be done before I can get to writing about the actual science.

Revisions to A Justifiable Investment in AI for Healthcare paper. A couple of months ago I pre-printed this paper that myself and Kass Karpathakis co first-authored. This week we got the peer review comments back. Happily they were relatively minor and so I worked on these and resubmitted the paper. The abstract is below as is the definition of ‘justifiable ROI” that I added following a helpful reviewer prompt.

Abstract: Healthcare systems are grappling with critical challenges, including chronic diseases in aging populations, unprecedented health care staffing shortages and turnover, scarce resources, unprecedented demands and wait times, escalating healthcare expenditure, and declining health outcomes. As a result, policymakers and healthcare executives are investing in artificial intelligence (AI) solutions to increase operational efficiency, lower health care costs, and improve patient care. However, current level of investment in developing healthcare AI among members of the Global Digital Health Partnership (GDHP) does not seem to yield a high return yet. This is mainly due to underinvestment in the supporting infrastructure necessary to enable the successful implementation of AI. If a healthcare-specific AI winter is to be avoided, it is paramount that this disparity in the level of investment in the development of AI itself and in the development of the necessary supporting system components is evened out.

Definition: “The implementation gap raises the question of whether AI is currently providing a justifiable return on investment (ROI) based on its ability to provide direct: (a) patient value in terms of improvements in experience and outcomes; (b) healthcare service value in terms of improvements in public health and worker satisfaction; (c) financial value to the healthcare system in terms of reductions in costs; (d) operational value in terms of improvements in efficiency; (e) strategic value in terms of meeting healthcare system goals; and (f) risk/benefit value in terms of maximizing the benefits while proactively mitigating the risks of AI use for healthcare.”

Things I did

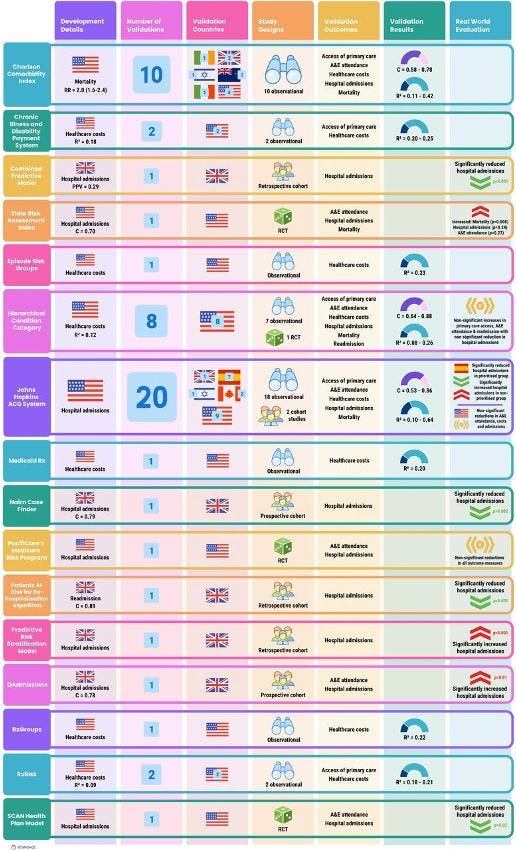

Published a systematic review examining the real world effectiveness of population health risk stratification algorithms. My colleagues, Christopher Oddy, Joe Zhang and Hutan Ashrafian, and I found that results from the real-world application of population health risk-prediction models are disappointing with equal weight of evidence suggesting a harmful effect as a beneficial one. Structured abstract below.

Objectives Risk stratification tools that predict healthcare utilisation are extensively integrated into primary care systems worldwide, forming a key component of anticipatory care pathways, where high-risk individuals are targeted by preventative interventions. Existing work broadly focuses on comparing model performance in retrospective cohorts with little attention paid to efficacy in reducing morbidity when deployed in different global contexts. We review the evidence supporting the use of such tools in real-world settings, from retrospective dataset performance to pathway evaluation.

Methods A systematic search was undertaken to identify studies reporting the development, validation and deployment of models that predict healthcare utilisation in unselected primary care cohorts, comparable to their current real-world application.

Results Among 3897 articles screened, 51 studies were identified evaluating 28 risk prediction models. Half underwent external validation yet only two were validated internationally. No association between validation context and model discrimination was observed. The majority of real-world evaluation studies reported no change, or indeed significant increases, in healthcare utilisation within targeted groups, with only one-third of reports demonstrating some benefit.

Discussion While model discrimination appears satisfactorily robust to application context there is little evidence to suggest that accurate identification of high-risk individuals can be reliably translated to improvements in service delivery or morbidity.

Conclusions The evidence does not support further integration of care pathways with costly population-level interventions based on risk prediction in unselected primary care cohorts. There is an urgent need to independently appraise the safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of risk prediction systems that are already widely deployed within primary care.

Turned thesis into 80 minute video/podcast. As we rapidly approach London data week and the national election, I have been asked several times a version of the question “what should the next government do to make AI work in the NHS?” This was essentially the topic of my PhD thesis “Designing an Algorithmically Enhanced NHS” which is online here. In an effort to make it a bit more accessible, I recorded an 80 minute video version which is on YouTube below. Slides, Acknowledgements, full list of policy papers.

Reviewed 4 papers. In the never-ending academic game of you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours, I reviewed four articles for the BMJ and AI and Society.

Research interview for NHS AI Lab evaluation. The NHS AI Lab programme is currently being independently evaluated. I was interviewed by the evaluators about the process of setting it up (I was there at the beginning) and what I think it has/ has not achieved since. I shall be very interested to see what comes out of the evaluation. What came up during that interview, is that not everybody is aware of the very complex relationships between different NHS bodies (those still in existence and those now defunct) and how these relationships can make achieving the aims of large-scale projects very difficult. So in a nutshell, with regards to data/AI:

The Department of Health and Social Care sets national level health policy and strategy (i.e., the health and social care data strategy Data Saves Lives); gives NHSE and all other NHS arms length bodies their annual mandate, determines the budget for each organisation; and is the only institution that has any ‘legal’ power i.e., if there are any changes required to the law - this must go through the Department of Health and Social Care.

NHS England is the commissioning body and decides where the money for the NHS is spent at a meso level - i.e., how much is spent on services etc. and what goes where, not necessarily how it is spent at a local level; sets NHS-level policy and strategy (i.e the NHS Long-Term Plan); it has to make these decisions in accordance with the mandate and budget provided by DHSC and reports to DHSC on its delivery against these objectives

NHS Digital was the delivery body and responsible for setting specialised policy (e.g., cybersecurity requirements for the NHS) and delivering specific services/products that were set out by NHS England in response to the mandate/strategy set by DHSC. To take the NHS App as an example: DHSC set the policy and strategy stating that it wanted the app to exist and what functions it should have, it made NHSE responsible for making sure that the app came into being, NHSE commissioned the app from NHSD which then brought in a consultancy to help build the technical infrastructure, local level policy for making it work e.g., all GP practices must integrate with the app by X date was set by NHSE, and DHSC was/is responsible for any legal changes required to make it work and holding NHSE & NHSD to account for bringing it into fruition.

The Health Research Authority is responsible for ethical approval of research projects involving data - including research projects that might involve the development of AI - i.e., it determines when a project is research vs. service delivery vs. direct care, and it determines when it is permissible to access data without explicit consent.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency is responsible for software as a medical device regulations and so determines when an algorithm, software code etc. app, falls within the definition of a medical device and what standards it must meet (in terms of effectiveness, safety, cybersecurity etc.) in order to be compliant with the regulations. It does not assess individual software to see if it is compliant (i.e., if that software is worthy of receiving a UKCA mark) - that is done by approved notified bodies.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence is responsible for Health Technology Assessment and making recommendations to the NHS with regards to whether or not a particular ‘treatment’ or ‘intervention’ should be made available on the NHS and whether it should be included as part of a national treatment guideline. These decisions are based on real world effectiveness evidence and cost effectiveness. For a new treatment or intervention to be recommended by NICE it needs to be more effective and efficient than the current gold standard of care for the relevant condition. To help NICE do this, it also therefore responsible for things such as the evidence standards for digital health technologies.

The Care Quality Commission is responsible for ensuring care provided by registered health and care organisations meets the standard of excellence expected.

A single algorithm capable of e.g., diagnosing breast cancer, would come into contact with each of these different bodies at different parts of its development-deployment-ongoing monitoring pipeline, and it is very rare that all these different bodies agree….

Things I thought about

The need for specialist ‘digital’ agencies/regulators. At least once a week I either find myself reading or writing a paper that says something like “existing regulator X should take on new function Y to ensure digital tech Z is safe, effective etc.” Such arguments arise from a very pressing need to more stringently govern digital health technologies in all forms - from wearables to apps to information posted on social media - and a desire to not add additional complexity to an already confused system (see above). However, I am increasingly of the opinion that this is going to result in regulatory bodies that are just spread far too thin and will not have either the resources nor the skills to cope with all their new responsibilities. Consequently, I am becoming more convinced that we need to take ‘digital’ or ‘software’ out of the existing analogue regulators where these responsibilities have been ‘tagged’ on in sometimes ill-fitting ways and create new specialist agencies that take on the end-to-end responsibility for digital/software products. For example, with diagnostic algorithms, I think we are approaching the point where we need a Healthcare Software Regulatory Agency that takes the fragmented responsibility for governing healthcare software off the MHRA, HRA, NICE, CQC and brings it all together in one place. So there is just one body responsible for governing healthcare software. Obviously the details of this would need careful thought, but I do not think we can continue the trend of continually adding responsibilities (or suggesting that we add additional responsibilities) to organisations that are not equipped to take them on and are already too stretched.

(A selection of) Things I read

Most of these are for the paper I’m writing about the rapid digitisation of healthcare and some are papers I’ve read before but needed to remind myself of.

Abdullahi, Aisha Muhammad, Rita Orji, and Abdullahi Abubakar Kawu. “Gender, Age and Subjective Well-Being: Towards Personalized Persuasive Health Interventions.” Information 10, no. 10 (2019): 301

Abernethy, Amy, Laura Adams, Meredith Barrett, Christine Bechtel, Patricia Brennan, Atul Butte, Judith Faulkner, Elaine Fontaine, Stephen Friedhoff, and John Halamka. “The Promise of Digital Health: Then, Now, and the Future.” NAM Perspectives 2022 (2022).

Aboueid, Stephanie, Samantha Meyer, James R Wallace, Shreya Mahajan, and Ashok Chaurasia. “Young Adults’ Perspectives on the Use of Symptom Checkers for Self-Triage and Self-Diagnosis: Qualitative Study.” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 7, no. 1 (2021): e22637.

Abul-Fottouh, D., M.Y. Song, and A. Gruzd. “Examining Algorithmic Biases in YouTube’s Recommendations of Vaccine Videos.” International Journal of Medical Informatics 140 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104175.

Alberto, Isabelle Rose I., Nicole Rose I. Alberto, Arnab K. Ghosh, Bhav Jain, Shruti Jayakumar, Nicole Martinez-Martin, Ned McCague, Dana Moukheiber, Lama Moukheiber, and Mira Moukheiber. “The Impact of Commercial Health Datasets on Medical Research and Health-Care Algorithms.” The Lancet Digital Health 5, no. 5 (2023): e288–94.

Alper, Meryl, Jessica Sage Rauchberg, Ellen Simpson, Josh Guberman, and Sarah Feinberg. “TikTok as Algorithmically Mediated Biographical Illumination: Autism, Self-Discovery, and Platformed Diagnosis On# Autisktok.” New Media & Society, 2023, 14614448231193091.

Alevizou, Panayiota, Nina Michaelidou, Athanasia Daskalopoulou, and Ruby Appiah-Campbell. “Self-Tracking among Young People: Lived Experiences, Tensions and Bodily Outcomes.” Sociology, 2023, 00380385231218695.

Andorno, R. (2004). The right not to know: an autonomy based approach. Journal of Medical Ethics, 30(5), 435. doi:10.1136/jme.2002.001578

Baker, Stephanie Alice. “Alt. Health Influencers: How Wellness Culture and Web Culture Have Been Weaponised to Promote Conspiracy Theories and Far-Right Extremism during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 25, no. 1 (2022): 3–24.

Bailey, Simon, Dean Pierides, Adam Brisley, Clara Weisshaar, and Tom Blakeman. “Dismembering Organisation: The Coordination of Algorithmic Work in Healthcare.” Current Sociology 68, no. 4 (2020): 546–71.

Basch, Corey H, Charles E Basch, Grace C Hillyer, and Zoe C Meleo-Erwin. “Social Media, Public Health, and Community Mitigation of COVID-19: Challenges, Risks, and Benefits.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 24, no. 4 (April 12, 2022): e36804. https://doi.org/10.2196/36804.

Cahan, Eli M., Tina Hernandez-Boussard, Sonoo Thadaney-Israni, and Daniel L. Rubin. “Putting the Data before the Algorithm in Big Data Addressing Personalized Healthcare.” NPJ Digital Medicine 2, no. 1 (2019): 78.

Catlaw, T. J., & Sandberg, B. (2018). The Quantified Self and the Evolution of Neoliberal Self-Government: An Exploratory Qualitative Study. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 40(1), 3-22. doi:10.1080/10841806.2017.1420743

Chinn, Sedona, Ariel Hasell, and Dan Hiaeshutter-Rice. “Mapping Digital Wellness Content: Implications for Health, Science, and Political Communication Research.” Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media 3 (2023): 1–56.

Coghlan, Simon, and Simon D’Alfonso. “Digital Phenotyping: An Epistemic and Methodological Analysis.” Philosophy & Technology 34, no. 4 (2021): 1905–28.

Cotter, Kelley, Julia R DeCook, Shaheen Kanthawala, and Kali Foyle. “In FYP We Trust: The Divine Force of Algorithmic Conspirituality.” International Journal of Communication 16 (2022): 1–23.

De Boer, Christopher, Hassan Ghomrawi, Suhail Zeineddin, Samuel Linton, Soyang Kwon, and Fizan Abdullah. “A Call to Expand the Scope of Digital Phenotyping.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 25 (2023): e39546.’’

D’Hotman, Daniel, and Jesse Schnall. “A New Type of ‘Greenwashing’? Social Media Companies Predicting Depression and Other Mental Illnesses.” The American Journal of Bioethics 21, no. 7 (July 3, 2021): 36–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2021.1926583.

Dionne, Émilie. “Algorithmic Mediation, the Digital Era, and Healthcare Practices: A Feminist New Materialist Analysis.” Global Media Journal: Canadian Edition 12, no. 1 (2020).

Dunn, Adam G, Kenneth D Mandl, and Enrico Coiera. “Social Media Interventions for Precision Public Health: Promises and Risks.” NPJ Digital Medicine 1, no. 1 (2018): 47.

Eagle, Tessa, and Kathryn E Ringland. “‘You Can’t Possibly Have ADHD’: Exploring Validation and Tensions around Diagnosis within Unbounded ADHD Social Media Communities,” In The 25th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS '23), October 22--25, 2023, New York, NY, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA 17 Pages.

Elias, Ana Sofia, and Rosalind Gill. “Beauty Surveillance: The Digital Self-Monitoring Cultures of Neoliberalism.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 21, no. 1 (2018): 59–77.

Engelmann, Lukas. “Digital Epidemiology, Deep Phenotyping and the Enduring Fantasy of Pathological Omniscience.” Big Data & Society 9, no. 1 (2022): 20539517211066451.

Eustace, S. (2018). Technology-induced bias in the theory of evidence-based medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(5), 945–949. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12972

Faden, R. R., Kass, N. E., Goodman, S. N., Pronovost, P., Tunis, S., & Beauchamp, T. L. (2013). An Ethics Framework for a Learning Health Care System: A Departure from Traditional Research Ethics and Clinical Ethics. Hastings Center Report, 43(s1), S16-S27. doi:10.1002/hast.134

Flahault, A., Geissbuhler, A., Guessous, I., Guérin, P., Bolon, I., Salathé, M., & Escher, G. (2017). Precision global health in the digital age. Swiss medical weekly, 147, w14423. doi:10.4414/smw.2017.14423

Floridi, L. (2016). Faultless responsibility: on the nature and allocation of moral responsibility for distributed moral actions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSTA.2016.0112

Forbat, L., Maguire, R., McCann, L., Illingworth, N., & Kearney, N. (2009). The use of technology in cancer care: Applying Foucault's ideas to explore the changing dynamics of power in health care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(2), 306-315. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04870.x

Forgie, Ella M E, Hollis Lai, Bo Cao, Eleni Stroulia, Andrew J Greenshaw, and Helly Goez. “Social Media and the Transformation of the Physician-Patient Relationship: Viewpoint.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 23, no. 12 (December 24, 2021): e25230. https://doi.org/10.2196/25230.

Gaeta, Amy. “Diagnostic Advertisements: The Phantom Disabilities Created by Social Media Surveillance.” First Monday, 2023.

Gran, Anne-Britt, Peter Booth, and Taina Bucher. “To Be or Not to Be Algorithm Aware: A Question of a New Digital Divide?” Information, Communication & Society 24, no. 12 (2021): 1779–96.

Green, Sara, and Mette N Svendsen. “Digital Phenotyping and Data Inheritance.” Big Data & Society 8, no. 2 (2021): 20539517211036799.

Laacke, S., R. Mueller, G. Schomerus, and S. Salloch. “Artificial Intelligence, Social Media and Depression. A New Concept of Health-Related Digital Autonomy.” American Journal of Bioethics 21, no. 7 (2021): 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1863515.

Laestadius, Linnea I, and Megan M Wahl. “Mobilizing Social Media Users to Become Advertisers: Corporate Hashtag Campaigns as a Public Health Concern.” Digital Health 3 (2017): 2055207617710802.

Lupton, D. (2013). Quantifying the body: Monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies. Critical Public Health, 23(4), 393-403. doi:10.1080/09581596.2013.794931

Martinez-Martin, Nicole, Henry T Greely, and Mildred K Cho. “Ethical Development of Digital Phenotyping Tools for Mental Health Applications: Delphi Study.” JMIR mHealth and uHealth 9, no. 7 (2021): e27343.

McAuliff, K., Viola, J. J., Keys, C. B., Back, L. T., Williams, A. E., & Steltenpohl, C. N. (2014). Empowered and disempowered voices of low-income people with disabilities on the initiation of government-funded, managed health care. Psychosocial Intervention, 23(2), 115-123. doi:10.1016/j.psi.2014.07.003

Murray, S. J. (2007). Care and the self: Biotechnology, reproduction, and the good life. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 2(1). doi:10.1186/1747-5341-2-6

Nan, Xiaoli, Yuan Wang, and Kathryn Thier. “Why Do People Believe Health Misinformation and Who Is at Risk? A Systematic Review of Individual Differences in Susceptibility to Health Misinformation.” Social Science & Medicine 314 (December 2022): 115398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115398.

Oudin, Antoine, Redwan Maatoug, Alexis Bourla, Florian Ferreri, Olivier Bonnot, Bruno Millet, Félix Schoeller, Stéphane Mouchabac, and Vladimir Adrien. “Digital Phenotyping: Data-Driven Psychiatry to Redefine Mental Health.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 25 (2023): e44502.

Powles, Julia, and Hal Hodson. “Google DeepMind and Healthcare in an Age of Algorithms.” Health and Technology 7, no. 4 (2017): 351–67.

Raymond, N. (2019). Safeguards for human studies can’t cope with big data. Nature, 568(7752), 277–277. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01164-z

Roetman, Sara. “Self-Tracking ‘Femtech’: Commodifying & Disciplining the Fertile Female Body.” AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research, 2020.

Richardson, V., Milam, S., & Chrysler, D. (2015). Is Sharing De-identified Data Legal? The State of Public Health Confidentiality Laws and Their Interplay with Statistical Disclosure Limitation Techniques. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 43(s1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12224

Schaffler, J., Leung, K., Tremblay, S., Merdsoy, L., Belzile, E., Lambrou, A., & Lambert, S. D. (2018). The Effectiveness of Self-Management Interventions for Individuals with Low Health Literacy and/or Low Income: A Descriptive Systematic Review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(4), 510-523. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4265-x

Schneble, Christophe Olivier, Bernice Simone Elger, and David Martin Shaw. “All Our Data Will Be Health Data One Day: The Need for Universal Data Protection and Comprehensive Consent.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22, no. 5 (2020): e16879.

Smith, G. J. D., & Vonthethoff, B. (2017). Health by numbers? Exploring the practice and experience of datafied health. Health Sociology Review, 26(1), 6-21. doi:10.1080/14461242.2016.1196600

Wellman, Mariah L. “‘A Friend Who Knows What They’re Talking about’: Extending Source Credibility Theory to Analyze the Wellness Influencer Industry on Instagram.” New Media & Society, 2023, 14614448231162064.

Zhu, Z., Yin, C., Qian, B., Cheng, Y., Wei, J., & Wang, F. (2019). Measuring Patient Similarities via a Deep Architecture with Medical Concept Embedding. ArXiv:1902.03376 [Cs, Stat]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.03376